As teachers, we all strive to maximise the potential of our classes, and we all want to develop our students’ academic curiosity in our subjects. We love what we teach and so we want others to love it too, and whilst we want our students to maximise their potential for their own grades, in the background there is also the need for value-added results. In my own teaching, I have often found that value-added is hardest to achieve with the most able, and my experience of external exam marking has shown me that no Grade 9 is ever a certainty.

My discussions with the Lower School Academic Awards Holders and other more able students aim to give them a forum to have academic discussions and debates of a kind that they may not have with their usual friendship groups, and they are invited to research and present on a topic of their choice that extends the usual KS3 curriculum. It is also a place where they can express any worries or concerns associated with being a scholar, and the group are very good at problem solving and providing reassurance to each other. In this article I aim to explore some of the key concerns that our more able junior students have so that we can strive to alleviate these worries, and to discuss some of the strategies that our scholars would like us to use to help them develop their curiosity and strive towards their full academic potential.

Giving feedback

Once an academic scholar myself, I will never forget the shame in reading the “18%” written on the front cover of my Year 10 Physics exam as it was placed on my desk. I knew that the exam hadn’t gone well and I had already evaluated the flaws in my revision, but I didn’t think that the result would be as low as that. Even though I learnt from my mistakes, the moment has forever remained significant to me.

Discussing this situation with the Lower School Academic Award Holders it is clear the majority of them hold a huge fear of this scenario happening. Indeed, many were already able to recall events from just their short time at Downe House where their non-award-holding peers had taken great joy from seeing a face-up paper reveal that they had ‘beaten’ an academic scholar. Their fear of failure is quite acute – it seems that many place this as sub-80 or even 85% – and it is important that we remember to consider the potential reactions of our more able pupils on receiving marks and feedback in the same way that we would carefully support our weaker students. They have very high expectations of themselves and may struggle with the reality that despite being an academic scholar, they will not necessarily score most highly in every class. They worry what the implications of a poor result will be, and I have repeatedly had to reassure these students that a few disappointing results does not mean that they will have their award taken away from them, and that provided they are working hard, both we and their parents will continue to be proud of them.

Whilst these young students mature and learn to self-evaluate in a positive way, please do assist in the mitigation of their anxieties by providing reassurance if they feel disappointed in a result, and by giving constructive feedback so that they can learn from their mistakes and feel confident moving forwards. Tutors and House Staff are always on hand to offer them support and it is helpful if they can be aware of and echo the feedback, advice and reassurance that has been given in class.

Extension work

In a questionnaire, I asked eight of our KS3 Academic Scholars and Exhibitionists their thoughts and feelings about being award holders, and what they felt helped them best to maximise both their potential and interest. Above all else, it was clear that our more able KS3 students want to be challenged, most particularly with extension work that is readily available to them on the page, without having to be asked for: they would prefer not to draw attention to the fact that they would like more work!

When offering extension work, however, Anstee (2013, p102) urges teachers to consider its quality rather than quantity: “There’s no incentive to do MOTS [More of the Same] – repeating what you’ve just done is dull and a waste of time. It can seem like a punishment for being too clever and the student learns not to finish as quickly next time. The challenge of HOTS [Higher Order Thinking Skills], however, is something to relish – a clear development of learning and, therefore, worthwhile.” It is key, therefore, for our extension work to offer tasks that are able to develop higher order thinking skills, rather than being another set of questions that are just more of the same (although I do appreciate that there are subjects that do benefit from this repetition).

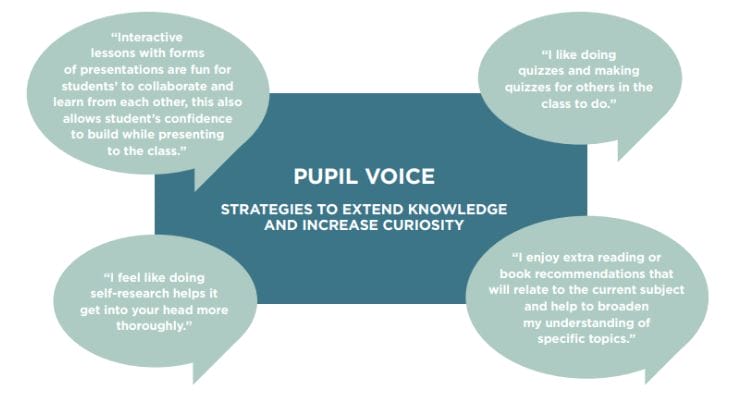

In their questionnaire, our scholars gave a whole range of suggestions of the types of activities that both engage their interest and offer them the chance to extend their knowledge, for example research opportunities, collaborative work (Smith, 2006), creating and giving presentations (Oxford University Press), Making quizzes for their peers (e.g. using Blooket), extended writing opportunities and wider reading recommendations.

Digital technology

I completed the 21st Century Learning Design pathway in 2023 purely as part of the requirement to renew my MIEE status. Essentially, I completed it to tick a box. Now that I have had the time to process the information that I learnt and to align it with the comments from our Academic Award Holders and academic research, I realise how relevant it is and how very lucky we are to have the technological opportunities at our fingertips every lesson that can enable us to easily maximise potential and develop curiosity. So many of the strategies requested by our Academic Award Holders were to be found in the modules of this pathway, and using the different Microsoft applications makes it so much easier for us to be able to provide opportunities for effective collaborative work, use quizzes and games to reinforce learning in a fun way, and research tasks of any length can be implemented with ease. I know that I have grown to take the educational benefits offered by our Surfaces for granted, but they are very real opportunities for developing curiosity and maximising potential with relative ease.

Able pupils learn best from experiences about which they are passionately interested and involved (Smith, 2006) and the strategies in the table diagram on the previous page should not only appeal to their interests but also serve to boost social skills through collaboration and confidence through public speaking. However, we must remember that whilst “errors are critical to learning” (Smith, 2006, p11) we must ensure that our students are able to do this in a safe and supportive environment so that they can learn positively from their mistakes rather than perceiving themselves to be a failure.

References

Anstee, P. (2013) Differentiation Pocket Book. Teachers’ Pocketbooks, Hampshire.

Darlington, H and Bell, D. (2018) From curiosity to interest: The use of effective pedagogy to develop students’ long-term interest (chartered.college)

Microsoft Learn, (2023). 21st century learning design – Training | Microsoft Learn.

Oxford University Press (2017) Creating Extension Activities (oup.com).

Smith, C. (2006). Principles of inclusion: Implications for able learners. P3-21 In Smith, C. 2006. Including the Gifted and Talented. Routledge, London.

‘Maximising Academic Potential and Developing Academic Curiosity Amongst our More Able KS3 Students‘ by Nicola Patrick, published in The Enquiry: Issue 7.

The Enquiry is a staff journal dedicated to reflections on educational research, and teaching and learning at Downe House School. Issue 7 was published in March 2024, looking back at Michaelmas term 2023.

All previous issues can be found here: The Enquiry by downehouseschool Stack – Issuu.